|

|

Despite several controversies that claim that the Taj Mahal was designed by an Italian Geronimo Veroneo, or a French silversmith Austin de Bordeaux, the first real evidence of the architect's identity emerged in the 1930s when a seventeenth century manuscript called the Diwan-i-Muhandis was found to mention the Taj Mahal. This manuscript contains a collection of several poems written by Luft Allah, including several verses in which he describes his father, Ustad Ahmad from Lahore, as the architect of the Taj Mahal and the Red Fort at Delhi. Ahmad was a Persian engineer-astrologer. Luft Allah also states that Shah Jehan conferred upon his father the title "Nadir al-Asr" (the Wonder of the Age); unfortunately court histories do not corroborate this claim. Other sources record that Ustad Ahmad was one of the architects of the Red Fort. Further evidence has been found of other large projects undertaken by Ustad Ahmad, strengthening the plausibility of his son's claim. It is interesting to note that Ustad Ahmad had a number of aliases : Ustad Khan Effendi, Ustad Mohammed, Isa Khan, Isa Effendi and a number of permutations of the name - fictional amalgam of Muslim sounding names, most likely the invention of latter-day British guidebook writers.

It

must be emphasised that the design of the Taj Mahal cannot be ascribed

to any single master-mind. The Taj is the culmination of an evolutionary

process. It is the perfected stage in the development of Mughal

architecture. The names of many of the builders who participated in the

construction of the Taj in different capacities have come down to us

through Persian sources. A project as ambitious as the tomb of Mumtaz

Mahal demanded talent from many quarters. From turkey came Ismail Khan a

designer of hemispheres and the a builder of domes. Qazim Khan, a native

of Lahore travelled to Agra to cast the solid gold finial that crowned

the Turkish master's dome. Chiranjilal, a local lapidary from Delhi was

chosen as the chief sculptor and mosaicist. Amanat Khan from Shiraz was

the chief calligrapher, and this fact is attested on the Taj gateway

where his name has been inscribed at the end of the inscription.

Muhammad Hanif was the Supervisor of masons, while Mir Abdul Karim and

Mukkarimat Khan of Shiraz handled finances and the management of daily

production. Sculptors from Bukhara, calligraphers from Syria and Persia,

inlayers from South India, stonecutters from Baluchistan, a man who

specialised in building turrets, another who carved only marble flowers

- thirty seven men in all formed the creative nucleus, and to this core

was added a labour force of twenty thousand workers recruited from

across North India.

It

must be emphasised that the design of the Taj Mahal cannot be ascribed

to any single master-mind. The Taj is the culmination of an evolutionary

process. It is the perfected stage in the development of Mughal

architecture. The names of many of the builders who participated in the

construction of the Taj in different capacities have come down to us

through Persian sources. A project as ambitious as the tomb of Mumtaz

Mahal demanded talent from many quarters. From turkey came Ismail Khan a

designer of hemispheres and the a builder of domes. Qazim Khan, a native

of Lahore travelled to Agra to cast the solid gold finial that crowned

the Turkish master's dome. Chiranjilal, a local lapidary from Delhi was

chosen as the chief sculptor and mosaicist. Amanat Khan from Shiraz was

the chief calligrapher, and this fact is attested on the Taj gateway

where his name has been inscribed at the end of the inscription.

Muhammad Hanif was the Supervisor of masons, while Mir Abdul Karim and

Mukkarimat Khan of Shiraz handled finances and the management of daily

production. Sculptors from Bukhara, calligraphers from Syria and Persia,

inlayers from South India, stonecutters from Baluchistan, a man who

specialised in building turrets, another who carved only marble flowers

- thirty seven men in all formed the creative nucleus, and to this core

was added a labour force of twenty thousand workers recruited from

across North India. Material Used

Along with the labourers flocking to Agra, materials for construction also began arriving : principally red sandstone from local quarries and marble dug from the hills of far-off Makrana, slightly southwest of Jaipur in Rajasthan. Although the treasury was well filled, such prodigious quantities of rare stuffs were required that caravans travelled to all corners of the empire and beyond in search of precious materials. From Chinese Turkestan in Central Asia came Nephrite jade and crystal; from Tibet, turquoise; from upper Burma, yellow amber; from Ba

dakhshan

in the high mountains of northeastern Afghanistan, lapis lazuli; from

Egypt, chrysolite; from the Indian Ocean, rare shells, coral, and

mother-of-pearl. Topazes, onyxes, garnets, sapphires, bloodstone, forty

three types of gems in all - ranging in depth from Himalayan quartz to

Golconda diamonds - were ultimately to be used in embellishing the Taj

Mahal.

dakhshan

in the high mountains of northeastern Afghanistan, lapis lazuli; from

Egypt, chrysolite; from the Indian Ocean, rare shells, coral, and

mother-of-pearl. Topazes, onyxes, garnets, sapphires, bloodstone, forty

three types of gems in all - ranging in depth from Himalayan quartz to

Golconda diamonds - were ultimately to be used in embellishing the Taj

Mahal. In order to transport the marble, a ten mile long ramp of tamped earth was built through Agra, and on it trudged an unending parade of elephants and bullock carts dragging blocks of marble to the building site. Once the marble reached the Taj, it was hoisted into place by means of an elaborate post-and-beam pulley manned by teams of mules and masses of workers tugging and hauling.

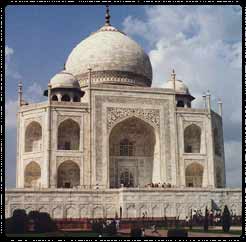

The first buildings to be constructed were the tomb proper and the two mosques that flank it; then came the four minarets; finally the gateway and auxiliary buildings were erected. All were built as integral parts of a single unit, carefully planned to harmonise, for a law of Islam decrees that once a tomb is completed nothing can be added to it and absolutely nothing can ever be taken away from it.